The Curious Story of How Sake Became the Drink We Know Today

Sake the way we know it today is radically different from how it was made throughout the thousands of years of Japan’s history. Only in the last 100 years or so have technology, consumer trends, unfortunate circumstances, bad decision making, and finally a new generation of experimentation-friendly brewers come together to create the sake we know today.

A Disputed Origin

From mouth-chewed rice to being imported from China, the origins of sake are theories ranging from the quirky to the expected. No one really knows exactly when or how sake came into existence though.

One popular, if unappetizing, theory is that uncooked rice was simply chewed on (as the enzymes in saliva break down starch into sugar), spat out, and then left to naturally ferment overnight.

This was a popular method for making alcoholic beverages around Asia so would seem plausible.

Other theories include brewing up rice that was simply forgotten and became moldy to being imported from China, where much of Japanese culture originated anyway.

Whatever the reality, the first actual records of sake reach back to the 8th century when the Japanese capital was in Nara. During this time an official “department of sake” was responsible for creating sake that was used in Shinto rites.

Rice polishing was difficult and not common, and sometimes even rice bran (the “skin” of the rice) was used, so the beverage itself was quite different from the usually delicate drink we find today.

Sake Starts to Resemble Sake

It took all the way until the Edo period (1603-1868), which was when the Tokugawa clan ruled Japan, and a period of relative peace and prosperity endured, that the sake industry developed some of the main structures we still find today.

Sake production switched from being made five times per year to only being made in winter, heat sterilization first occurred (300 years before Louis Pasteur discovered the effect of pasteurization), the Toji system of brewmasters was created and filtering sake became commonplace.

The Meiji Era

When the Tokugawa shogunate that ruled the country since the beginning of the 17th century (the Edo period) came to an end and was replaced by the Meiji government in 1868, the government undertook radical reforms regarding taxation and land ownership. Citizens could own land for the first time and landowners instead of farmers became responsible for paying taxes.

Large-scale changes usually create winners and losers and this case was no different. So in order to prevent rioting by those that lost out, the new Japanese government gradually reduced land taxes.

To replace the reduced land taxes, however, the Meiji government needed to come up with a new revenue source, which it found in liquor taxes. It also allowed anyone with capital to start brewing sake.

The result was that by 1904, at the time of the Russo-Japanese war, sake taxes made up a whopping 30% of the government’s total tax revenue, an incredible sum in today’s terms.

As one can imagine, due to the importance of sake as a revenue source, changes to sake followed swiftly.

In order to increase quality (and thus sales and revenue), the Japanese government introduced a multitude of measures: standardizing processes and starter cultures, isolating and culturing the best yeasts, and creating the National New Sake Awards, which mark its 110th anniversary in 2021.

But it was not all good news. Due to the difficulty of collecting taxes on it, “doburoku”, which was the homebrewed sake that was popular with farmers and peasants and considered an ancient tradition, was outlawed.

Overall, however, the many changes made a positive impact on the quality of sake.

Sake in WW2 and the after-war period

The trend towards better sake came to an abrupt end with the beginning of the second world war.

Sake as we know is made from rice, which is also the staple food of Japan, and with looming rice shortages other ways of making sake had to be found.

The result was “Sanzo-shu”, which was essentially sake with added alcohol, water, MSG, saccharides, and acids and, while being perhaps a necessity for the times, helped bring about the radical decline of sake several decades later.

Along with the rise of Sanzo-shu, this period saw a halving of the total numbers of breweries in existence, from 8000 to 4000, and the rise of bootleg liquor in order to escape the continuously increasing taxes on the production and sale of sake.

Before sake’s eventual decline, however, the after-war period brought another boom to sake consumption.

Aided by refrigerators, year-round cooling became commonplace, cup sake was launched and restrictions for purchasing sake were lifted. Along with the rising wealth of Japan, demand for sake soared and reached a high of 17.6 million hectolitres in 1973.

Westernization helps seal sake’s decline

Since then sake has been in a steady decline. It made up around 98% of all liquor sales at the end of the 19th century, 30% in 1970 but nowadays only constitutes some 6.5%.

One major reason for the decline of sake consumption was simply the westernization of Japan: beer became popular along with the refrigerator and then even more when canned beer was invented.

Wine became fashionable and whisky as well, along with shochu and cocktails made from a number of spirits. These products were all new and trendy and sake had the unfortunate image of being a drink for drunkards and old men, the large 1.8L bottles being associated with heavy drinking, especially by the younger generation.

This worsening image of sake was the other major contributing factor to the decline of sake. The Sanzo-shu, a remnant of the necessities of the second world war, never stopped being produced, even when rice became plentiful again. A cheap, highly profitable brew for brewers, it was however associated with causing hangovers.

A bad image, marketing mishaps, and increasingly fashionable foreign drinks sealed the deal and since the 1970s sake consumption has never stopped declining in Japan. Only some 1’200 active breweries remain nowadays, compared with 8’000 in the pre-WW2 period and compared with over 90’000 wineries in France.

Another remnant of wartime decision-making was the tax system for sake, by which the “grade” of sake was determined simply by the amount of tax paid on the product, rather than on the quality or any other subjective or objective criteria. A second-rate sake could thus be just as good, or even better than a first-rate sake. This was eventually (and fortunately) revised.

The Ginjo Boom and the Establishment of Premium Sake

It was enterprising breweries rather than the government that first started coming up with better solutions to the broken system of categorizing sakes by the amount of taxes paid.

Production methods such as Junmai, Ginjo, and Honjozo (which can be read about here), started being used and gave consumers the peace of mind of having objective standards linked to the production method of the sake they bought.

The government eventually followed suit and around 1990 abolished the taxation system and formally recognized the eight categories of premium sake that breweries had been using anyway.

The proliferation of mechanical polishing machines, a new type of sake yeast, the invention of a new type of brewing method that produced highly fragrant sake (Ginjo) then crossed with Japan’s bubble economy at the time and led, in the early 1980s, to a renaissance of sorts for sake, the “Ginjo boom”.

Highly fragrant, clean, and smooth to drink, ginjo remains popular today and usually dominated the sake press.

But all of that still couldn’t stop the overall decline of sake.

Only recently has a small sliver of the market, the premium and experimental segment, seen signs of revival.

Part of this resurgence has to do with a new generation of brewers. Influenced by their experience with Western products like wine, and having spent time abroad, they are starting to rediscover the allure and the potential behind every level of sake (rather than just Ginjo) and are open to experimentation with different production methods.

New types of koji with higher acidity, a focus on blending, and experimentation with radically different rice types (such as red and black rice) are some of the methods we see being used in sake nowadays.

So while sake is still struggling, many experts think that sake will rise again. They are pointing to increased demand from across Asia and the US, to international sake competitions based on how well sake fits with western food, to sake breweries popping up in France and Australia and a host of other factors.

Whether sake will ever really become popular and be able to make the transition from niche product consumed in Japanese restaurants to the Western dinner table remains to be seen.

But it definitely deserves to be, as it provides a universally alluring flavor profile that is easy to match with food but radically different from wine or beer.

Interested in trying some of the sake that we mentioned in this article?

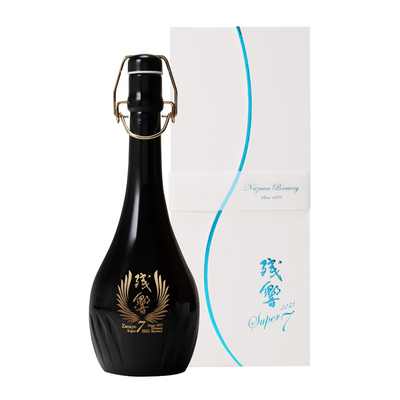

- A more traditional sake: Hanzo Junmai Daiginjo 'Kami No Ho'

- A typical ginjo-style sake; clear, smooth and aromatic: Echigo Sekkobai Junmai Daiginjo

- Junmai: Echigo Sekkobai Tokubetsu Junmai

- A modern type of sake: Hanzo & Ginpu

Leave a comment